The Cell Phone Debate

Apple released its first iPhone in June of 2007, a tech milestone that was overshadowed for me by my graduation from high school. I had no K-12 classroom experience with a smartphone, although my trusty Samsung SCH-A670 was always close at hand. In fact, I was seven months shy of completing my SECOND university degree before I was able to afford my first smartphone (this moment was actually documented on this blog). And while I do not have experience as a youth-learner with a smartphone, I do have experience teaching in the K-12 system with students who have smartphones, experience teaching adults with smartphones, and have been an adult learner with a smartphone. We’re 17 years out from the release of that first iPhone, nearly two decades have passed, and educators are still trying to communicate the role that these tools can play in their programming.

So let’s try and break down the available information to help us make an informed decision. If you have been following me for any length of time you will know that one of my approaches to education is that “there is not one way to incorporate educational technology”. You will not leave this blog post with an absolute answer of, “yes, students have a right to unrestricted access to a smartphone”, or, “no, smartphones should be banned during school hours”. These types of absolutes do not exist in society and, at best, we are faced with an endless sea of grey situations; neither black nor white and dependent on the unique context in front of us. What I do hope you leave with is a summary of resources that can help you make an informed decision on what role cell phones can play in your situation.

It is important to note that this post will utilize a variety of terms: smartphone, cell phone, mobile device (which could include wearables). These will be used interchangeably and essentially refer to an easily transportable device capable of connecting to the internet.

Despite their prevalence in our society, the debate over cell phone use in education rages on.

The Canadian Landscape

The Manitoba Framework for Learning is guided by five main principles, one of which is agility. This principle calls for educational programming that, “…will serve learners as they navigate and thrive in today’s world as well as in tomorrow’s” and mandates that our approach to teaching and learning, “…proactively adapts to changes in society”. With this principle in mind, I think it is important for us to have a strong understanding of what our society looks like in terms of cellphone access and usage. What does the Canadian landscape look like and how can we use this data to help ensure that we are proactively adapting our approach to education to align with this reality?

We Are Social is an organization focused on “understanding online culture and social behaviours” that releases a series of yearly reports that “highlights everything you need to know about social media, internet, mobile and e-commerce trends globally.” Although the 2024 report should be released shortly, their most current findings from January of 2023 showed that 93.8% of Canadian internet users between the ages of 16 and 64 have some type of mobile phone (2023, p. 25) and these users average 6 hours and 35 minutes of internet time every day (2023, p. 32). The full report slides are embedded below and I’ve highlighted slide 33 which provides a breakdown of the main reasons why users are accessing the internet.

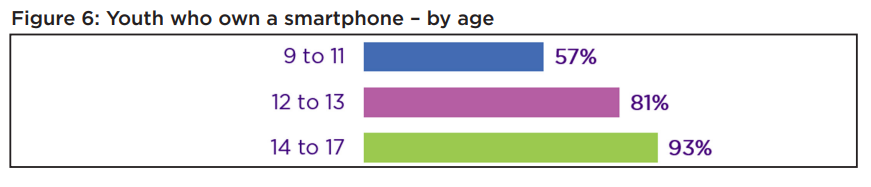

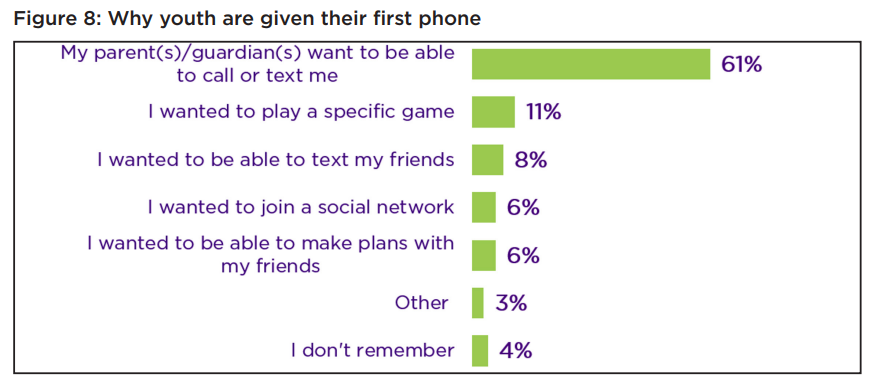

MediaSmarts, Canada’s Centre for Digital Media Literacy, has released a research series entitled Young Canadians in a Wired World which represents, “Canada’s longest-running and most comprehensive research study on young people’s attitudes, behaviours, and opinions regarding the internet, technology, and digital media.” This series, which began pre-Y2K has compiled data from over 20,000 parents, teachers, and students and covers a variety of topics. Their 2022 report, Life Online, found that smartphones are the most common device used to access the internet at 50% (2022, p. 13) with over 50% of students owning their own smartphone by the time they reach the grade 4-6 cohort. Interestingly enough, research completed by MediaSmarts echoed the findings of Pew that saw access to a smartphone be initiated by the child’s caregivers as a means to increase communication (2022, p. 15).

Digital Equity

The use of a personal device, such as a smartphone, can be an important component of closing the digital divide for school divisions. While some divisions/schools can fund and maintain a one-to-one ratio for their students, many fall short of this target. As such, supplementing school-provided inventories with student personal devices can increase overall access and implementation within the school/division. Think about it, rather than having to work with complicated logistics between staff to share digital resources to make sure teachers have enough for a class set of devices, which could lead to less use while they wait for all of the required devices to be available, teachers could effectively utilize a smaller number of school devices knowing that they have x-number of students who can also access on their personal device. Furthermore, it is quite common that the specs of a student-owned smartphone exceed those of the school laptops.

Having an option to utilize their personal device as part of school programming also provides students, and their caregivers, with an opportunity to see how they can utilize these tools within an educational or professional setting. This includes, but is not limited to:

- how to change settings on your device for personal management (notifications, sounds, calendar, display)

- educational software options

- accessibility tools

- privacy, security, and digital citizenship

For those wondering where to start with using student personal devices as part of their school plan, Manitoba Education has had a Bring Your Own Device Guide (BYOD) available for schools and divisions since 2014. While some aspects of this guide are outdated, it provides a helpful overview of how personal devices could be implemented purposefully into schools and speaks to some of the considerations that should be discussed on the macro- and micro-scales (ex: division-level versus school-level).

The option of utilizing personal devices, whether through a formal BYOD school program or not, not only helps increase access in classrooms but can also assist in the consistency of educational programming. The Covid-19 suspension of classes, and following restrictions, highlighted the following:

- 79% of rural students have access to some type of technology outside of schools (ICTC, 2021, p. 22)

- those with a higher device ratio adapt faster and experience fewer struggles (BU CARES, 2021, p. 34)

By providing the option for students to learn how to utilize a personal device for educational purposes, transitions to remote learning can be less disruptive. In instances where students are unable to be present in our buildings, and connectivity is available to them, the use of a personal device can be a tool to help increase access and reduce transition times.

*It is important to note that the use of personal devices is one option that may be available to students but this should not replace well-funded and maintained school-based inventories and supporting infrastructure.

Impact on Student Achievement

To start this section we need to frame our understanding of student achievement and what it means for a student to be “successful” within our system. The Manitoba Framework for Learning identifies that:

Learner success will look different for every child, but it always means they are prepared to reach their full potential and to live The Good Life in which they

https://www.edu.gov.mb.ca/k12/cur/framework/docs/frameworkforlearning_eng.pdf

• have hope, belonging, meaning, and purpose

• have a voice

• feel safe and supported

• are prepared for their individual path beyond graduation

• have capacity to play an active role in shaping their future and be active citizens

• live in relationships with others and the natural world

• honour and respect Indigenous ways of knowing, being, and doing with a commitment to and understanding of Truth and Reconciliation

You will notice that this definition of success or achievement does not speak to post-secondary participation or ranking on the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) organized by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Despite not being identified as a factor for success by Manitoba Education the PISA ranking, which currently sees Canada in the top 10 overall, is commonly used as a marker for student achievement by those outside the field of education. An identified concern stems from the fact that Canada and as an extension, Manitoba, has trended downward in our PISA ranking since the inception of the assessment in 2000. A correlation has been noted that this downward trend coincides with the rise in access to mobile devices. However, in that same period, Manitoba’s graduation rate has trended upward. So an important question is, are we looking to our local definition for success? Or to a third-party organization that focuses on economics?

Due to PISA’s prevalence in the societal discussion on student achievement, I wanted to share some quotations from the 2015 PISA research publication, Students, Computers and Learning: Making the Connection

the skills that are typically learned at school play a crucial role in determining whether a student adopts digital technology and can benefit from it.

Students, Computer and Learning: Making the Connection, 2015, p. 186

Empowering young people to become full participants in today’s digital public space, equipping them with the codes and tools of their technology-rich world, and encouraging them to use online learning resources – all while exploring the use of digital technologies to enhance existing education processes, such as student assessment (Chapter 7) or school administration – are goals that justify the introduction of computer technology into classrooms.

Students, Computer and Learning: Making the Connection, 2015, p. 186

And indeed, affordable and widespread ICT devices, particularly mobile phones, have created many opportunities to bring education, health and financial services to poor or marginalised populations

Students, Computer and Learning: Making the Connection, 2015, p. 188

While these statements speak to the opportunities afforded by the availability of technology, such as smartphones, you will notice that they fall short of indicating causation between their use and student achievement. In fact, PISA’s research echoes that of many studies that highlight that, “adding technology to K-12 environments does not improve learning. What matters is how it is used to develop knowledge and skills” (2009, Zucker and Light). This research shed light on what educators and leaders already know, “Technology can amplify great teaching, but great technology cannot replace poor teaching” (PISA, 2015, p. 190).

With this in mind, perhaps the best way to impact student achievement in the age of smartphones is to:

- commit to the “Agility” principle of the MB Framework for Learning

- provide purposeful and ongoing support for the professional growth of educators to help ensure they can, “proactively adapt to changes in society”

- work to address childhood poverty rates in Manitoba

- Manitoba is home to some of the highest child poverty levels in Canada; with four ridings in the Canadian top-30 list. The Campaign 2000 spring 2020 report, Broken Promise Stolen Futures: Child and Family Poverty in Manitoba, indicates that 85,000 children are living in poverty in Manitoba (Campaign 2000 MB Report Card, pg. 4); almost 45,000 of these are among the highest-risk in Canada (Campaign 2000 Riding by Riding Comparison, pg. 5).

- Read more HERE

- partner with caregivers (see section further down in this post)

Impact on Mental Health

Access to a device can play a key role in the mental health toolkit for youth and adults. The Mental Health Toolkit, provided by Healthy Child Manitoba, identifies several ways in which access to a tool such as a smartphone can be a strategy in one’s wellness plan. This includes:

- access Kids Help Phone (listed throughout the document)

- access crisis lines (listed throughout the document)

- increase a sense of safety if working with anxiety (pg 25)

- listen to music as part of a mindfulness routine (pg 29)

- access at-home and on-the-go coping apps (pg 41-42)

- connect with friends and family (pg 68)

Canadian research by Noronha et al (2021) looked specifically at mobile apps within Indigenous communities and found that they can play an important role in removing barriers to services as well as be an effective tool for promoting resilience skills. The use of a personal device allows users to access self-regulation management strategies and accessibility tools in a manner that blends seamlessly into the social landscape without identifying them publicly as “different”. For many, real-time access to these supports is key to their daily mental well-being and can be the difference between them remaining in an educational/social situation or leaving. These include access to a:

- dictionary

- calculator

- translator

- read-aloud function

- speech-text function

- music

- guided breathing/meditation services

- virtual counselor or support person

There are, however, concerns with access to technology that allows one to use the internet. Increased levels of technological use can impact healthy sleep patterns, time spent engaged in physical activity, and the development of face-to-face interpersonal skills. While this includes smartphones it is important to highlight that concerns arise from how and when this device might be used and not the presence of the device itself. Recent findings from Brodersen et al reported that youth with high screen time use on weekends were associated with higher levels of suicidal ideation while high weekday use was associated with higher levels of anxiety (2022, pg 34). They emphasize the significance of identifying the activities being performed via the device though as increased frequency of smartphone gaming was associated with a lower risk of depressive feelings (2022, pg 34). They recommend that any usage guidelines be developed in a way that takes into consideration both the positive and negative uses of what is now considered a universal device of our society.

The Role of Caregivers

If the research indicates that it is the caregivers/parents who are the ones initiating access to these types of devices, often for direct communication (see first section of this blog post) then we would be remiss to not include this stakeholder group in our discussion. One aspect that I feel is not talked about enough is that our current group of students represents the FIRST cohort whose parents grew up with access to the Internet. I know that in my case, as part of the “millennial” cohort, we very much had unfiltered and unsupervised access. We had to figure things out on our own and, by and large, did not have access to any type of formal guidance. In the span of a few years, I went from hearing the strong fear-based messaging of, “Do not talk to strangers on the internet”, to, “Use the internet to bring a stranger to you… and then get in their car”. It makes sense that a large proportion of this demographic would feel unprepared as to how to effectively support their children in this realm.

As shared in the first section of this blog post, users average 6 hours and 35 minutes of internet time every day (2023, p. 32). Research by Matthes et al (2021) shared that parents’ smartphone use will serve as a model for their children and heavy engagement on their own devices can directly impact the frequency with which their children interact with screens. Furthermore, 51% of students aged 13-17 share that their parent or caregiver is distracted by their smartphone while having a conversation with them (PEW, 2018). Adults need to reflect on how we utilize smartphones with and alongside the children in our lives so that we can help establish healthy practices that include balance and time for purposeful and focused face-to-face connection.

To build on the discussion surrounding student achievement, the OECD reported that there is an association between student engagement in school and student use of the internet outside of school. For students who identified as “extreme” internet users, logging six or more hours of use outside of school hours, they were twice as likely to feel lonely at school compared to those of “moderate” internet use (2018, p. 44). This “extreme” demographic also showed up late to school/class 45% of the time (2018, p 44). Their research also indicates that there is a correlation between internet use and socioeconomic status with disadvantaged students spending more time online at home than their counterparts (2018, p. 133). The research completed by PISA (introduced in the previous section) suggests that, “well-being at school is strongly related to the electronic media diet outside of school” (pg 189).

So we know that the devices are most likely coming from the adults and we know that they expect their children to have access to them for communication. We also know that caregivers may struggle with their own smartphone use which is then, in turn, impacting their child’s use. This, in turn, could be associated with aspects of school engagement and attendance. It is clear that the cell phone debate HAS to be coupled with not only support for students and educators but for caregivers as well. A holistic approach that supports all stakeholder levels can assist with effective implementation.

Resources that could assist caregivers in this area include:

- Media Smarts

- Common Sense Media: Parent Tips and FAQs

- US-based

- Includes app and media reviews, software guides, and supporting research to help caregivers make informed decisions

- Manitoba Parent Zone

- Manitoba government

- Includes discussions on screen time and usage for different age levels

Recommendations

While I have listed several recommendations through this piece I am left with a final list of thoughts. These concluding points are not in any set hierarchy:

- personal devices, such as cell phones, are a product of our society, and classrooms should model effective use and guide students in how to use these tools efficiently and responsibly

- avoid “black-and-white” policies that do not allow for flexibility

- develop and implement support for educators on how technology can be used to appropriately meet educational goals

- create site-based practices on how and when personal devices can fit into the larger educational ecosystem

- engage all stakeholders in this process

- identify and communicate clear expectations at all levels

- develop and implement support for caregivers on their role in device management and education

1 thought on “The Cell Phone Debate”