The Inequity of Remote Learning

The Covid-19 pandemic has forced schools around the world to rethink how education is delivered to our youth. It has also placed a magnifying glass on the number of social services provided by schools. No longer is the conversation simply centered on, “how are schools teaching children”. This dialogue opened up an often overlooked fact that schools have become not only centers of education but also that of nutrition, mental health, security, and facilitators of economic participation.

On September 8th, four days after a draft version was shared with school divisions, the province of Manitoba published the Manitoba Education Standards for Remote Learning. This publication was placed online without an accompanying news release, social media mention, or inclusion to the “Website Update” notification page. While this oversight in itself does not equate nefarious intentions the contents of this document leave a bad taste in ones mouth. The following is a critique of this document and a call for Manitoba Education to revisit these standards before our schools are faced with an Orange or Red scenario which would see a significant portion of Manitoba students engaged in distance learning (MB Ed Standards for Remote Learning, pg. 1).

Consistent Application

Manitoba Education states that this document was created to ensure a consistent application of remote learning across the province (pg. 2). However, one thing that has not been accounted for is a consistent home environment across the province to ensure that these standards are even possible for Manitoba families; not to mention sustainable. Manitoba’s 200,000+ students spread across ~650,000 square kilometers which represent a wide variety of geographical features including heavily forested regions, expansive bodies of water, and seasonal roadway infrastructure. Almost half the province, 44.3%, is located outside of large urban centers. These factors play a significant role in determining what type of internet connectivity is available and how much it may cost.

Geography aside, Manitoba is home to some of the highest child poverty levels in Canada; with four ridings in the Canadian top-30 list. The Campaign 2000 spring 2020 report, Broken Promise Stolen Futures: Child and Family Poverty in Manitoba, indicates that there are 85,000 children living in poverty in Manitoba (Campaign 2000 MB Report Card, pg. 4); almost 45,000 of these are among the highest risk in Canada (Campaign 2000 Riding by Riding Comparison, pg. 5). This is far from a consistent home environment.

Technology Requirements

As a minimum standard to engage in remote learning the province of Manitoba has stated that participants must have, “a laptop with a camera and internet” (pg. 3). Now this specifically uses the word laptop, not device. Given that the Canadian statistics indicate that 83% of internet users access a connection via a smart phone or tablet we are missing a large population if the mandate is set on laptop as the device requirement (We are Social, 2020, sl. 25). Device choice aside, are we to assume that the ~43% of Manitoba students who are living below the poverty line will have access to a both a reliable device and sufficient internet connection to engage in remote learning?

What many school divisions saw during the spring suspension of classes was the distribution of hard copy packages for those that either required or preferred them over online options. However, these new standards state that this practice, “should be minimized to the greatest extent possible” and only explored as an option after, “discussion with the school division” (pg. 3). For those without a laptop, Manitoba Education has shared that it will be the responsibility of the school division to ensure that technology is accessible to all students (pg. 3). Multiple school divisions in Manitoba loaned out devices during the spring suspension of classes but these inventories only stretch so far. While it can be challenging to gauge the exact number of available laptops that could be loaned out to students from Manitoba school divisions it can be assumed that demand outweighs supply.

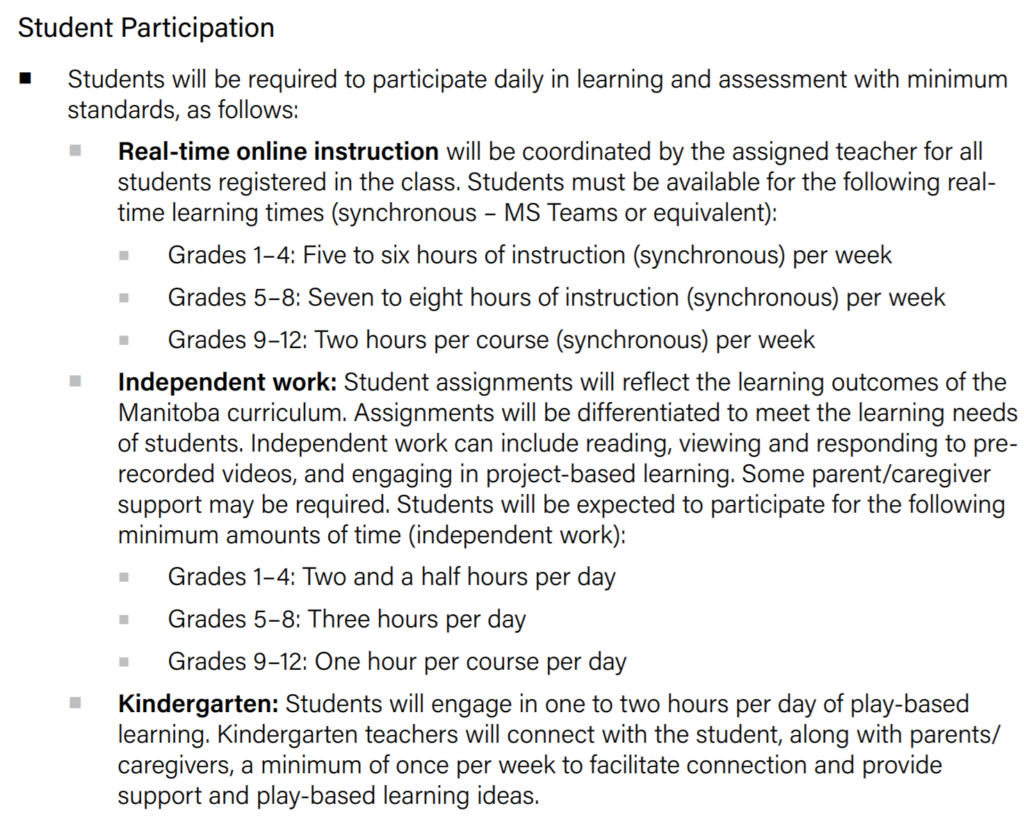

Student Participation

The provincial Standards for Remote Learning clearly outlines minimum expectations for student participation which are broken down into synchronous online experiences and independent work (which may or may not be online). Aside from the fact that these minimum expectations are unrealistic, seeing Gr 9-12 students slotted for 7 hours of work a day, the amount of data required to maintain this schedule is unsustainable (pg. 2).

The document itself uses Microsoft Teams as an example which multiple Manitoba school divisions offer through the MERLIN partnership. While it can vary depending on network, amount of people involved in the Teams meeting, and the content that is shared (video of the teacher versus embedded content) conservative estimates share that 1 hour of Teams meetings uses approximately 225MB of data. With a minimum of twenty monthly hours of synchronous online instruction for Gr 1-4 students, increasing to a minimum of forty monthly hours for Gr 9-12 students, that will require 4.5-9GB of data just for these minimums. This number does not factor in any additional independent work that may require an internet connection and will increase exponentially if families have more than one child involved in remote learning. This will quickly consume the data caps of the affordable plans provided through Bell MTS or Telus. Speaking from personal experience, once these data caps are breached the ability to work remotely is significantly impacted if not impossible.

The Manitoba Internet Divide

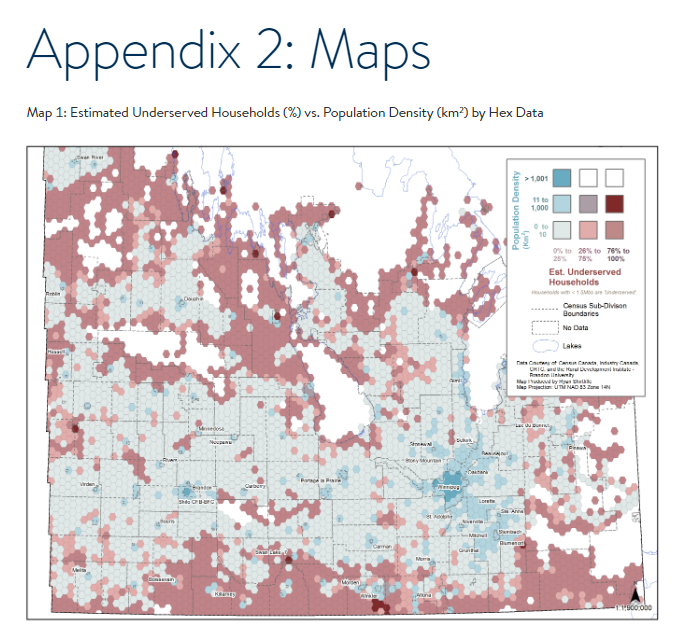

The current wording of this document clearly prioritizes online instruction. Not only does this place a heavy financial burden on families, and school divisions, to provide suitable laptops and internet connectivity to access educational programming but it may also be impossible depending on where one lives. Research completed by the Rural Development Institute out of Brandon University highlights just how many households are underserved when it comes to accessing internet sufficient to meet the minimums for remote learning (pg 10).

These numbers only increase as one moves into Northern Manitoba which is evident through the network coverage maps provided by Bell MTS, Telus, and Rogers. Given the stipulation that hard copy packages be, “minimized to the greatest extent possible”, the current standards directly discriminate against rural and northern Manitobans who do not have access to the same infrastructure enjoyed by their urban counterparts; regardless of how much they may be able to pay.

Call to Action

This critique clearly identifies that the Manitoba Education Standards for Remote Learning have not been designed with Manitobian families and students in mind. Whether it is the ~85,000 students living below the poverty line who may not be able to afford these requirements, the 44.3% of rural participants who may lack sufficient internet infrastructure, or the 83% who access via a smart phone or tablet, this plan excludes a significant proportion of Manitobian students from accessing equitable educational programming. As it currently stands, this plan divides our students into the “haves” and the “have nots”.

There is a significant population who may not be able to make remote learning work via online platforms. There is also a priority for the provincial government to ensure a consistent application for remote learning. Manitobians are encouraged to reach out to Minister Kelvin Goertzen and require:

- clearly outlined standards and expectations for remote learning for those without access to technology

- simply stating that “alternative plans” will need to be made does not remove the high priority placed on a system that is not equitable

- clarification on language choices surrounding laptops and cameras

- are other internet-enabled devices an option?

- what requirements are the government placing on camera-use within private homes?

- increased funding to either Manitobian School Divisions or to families to provide the devices and connectivity required to access pubic education programming

- delivery on promises to expand internet infrastructure to Manitobians in rural and northern areas

References

Campaign 2020. (2020). “Broken Promise Stolen Futures: Child and Family Poverty in Manitoba”. Retrieved September 14, 2020: https://spcw.mb.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Manitoba-Child-and-Family-Poverty-Report-2020.pdf

Campaign 2020. (2018). “Riding by Riding Analysais Shows Child Poverty in Canada Knows No Boundaries”. Retrieved September 14, 2020: https://campaign2000.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Campaign-2000-Riding-by-Riding-Child-Poverty-Report.pdf

Manitoba Education. (2019). “Enrollment Report”. Retrieved September 14, 2020: https://www.edu.gov.mb.ca/k12/finance/sch_enrol/enrolment_2019.pdf

Manitoba Education. (2020). “Manitoba Education Standards for Remote Learning,” Restoring Safe Schools. Retrieved September 14, 2020: https://www.edu.gov.mb.ca/k12/covid/docs/remote_learn_standards.pdf

Rural Development Institute. (2016). “A Call to Digital Action in Rural Manitoba,” Research Brief: State of Rural Information and Communication Technologies in Manitoba. Retrieved September 14, 2020: https://www.brandonu.ca/rdi/files/2016/11/RDI_Brief-DigAction-Sept5.16-FINAL.pdf

We Are Social. (2020). “Digital 2020 Canada”. Retrieved September 14, 2020: https://wearesocial.com/ca/digital-2020-canada/

Throughout Canada, Covid-19 has made it quite clear that we still have much to do if we want to create a society with good quality of life and equal opportunity for everyone. The information in this blog provided me with a much greater awareness of the inequities in Manitoba and in my own school division. Thanks.